undercover agent who finds his loyalty put to the test. In a nicely understated performance, Khurrana delivers his lines with a stoicism that recalls the suave charisma of 1970s Amitabh Bachchan even if, in this contemporary age, the angry young man no longer exists; he is weathered down, caged in a system that incites bloody unrest while simultaneously punishing those who fight for political autonomy.

Anek is a rare commercial film that spotlights Northeastern Indian stories, and goes out of its way to refuse to condemn guerrilla fighters as terrorists. Here, violence is not a spectacle, but rendered as the inevitable symptom of subjugation and intolerance. The film might be didactic in tone, but it is the kind of didacticism that injects political integrity into a cinematic landscape sorely lacking a backbone.

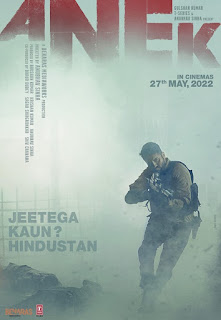

Anek is released on 27 May in cinemas.

… as you’re joining us today from India, we have a small favour to ask. Tens of millions have placed their trust in the Guardian’s fearless journalism since we started publishing 200 years ago, turning to us in moments of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. More than 1.5 million supporters, from 180 countries, now power us financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent.

Unlike many others, the Guardian has no shareholders and no billionaire owner. Just the determination and passion to deliver high-impact global reporting, always free from commercial or political influence. Reporting like this is vital for democracy, for fairness and to demand better from the powerful.

And we provide all this for free, for everyone to read. We do this because we believe in information equality. Greater numbers of people can keep track of the global events shaping our world, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action. Millions can benefit from open access to quality, truthful news, regardless of their ability to pay for it.

0 Comments